변재영 (KAIST 과학기술정책대학원 석사 졸업생)

jaeyoungbyon@gmail.com

대학 순위는 그 짧은 역사에도 불구하고 새로 갱신 될 때마다 큰 사회적 주목을 받는다. 그간 많은 사람들이 ‘순위’라고 하는 장치가 보편화되면서 얼마나 중요해졌는지, 그리고 그것이 고등 교육 전반에 미치는 영향은 무엇인지에 대한 우려를 표명한 바 있다. 이를 테면, 순위에 나타난 정보가 정확하다는 것을 어떻게 알 수 있을까? 대학 순위가 잘못 해석될 수 있음에도 불구하고 우리는 왜 이를 신뢰할까? 고등 교육기관은 이에 어떻게 반응했고, 이러한 반응은 경계해야 하는 것인가? 순위 제도는 암묵적인 방식으로 학계 및 고등 교육 관계자에게 상당한 영향을 미친다. 많은 대학이 순위 상으로 더욱 “활약”하기 위해 전체적인 학업 및 행정 구조를 재편했는데, 학계의 이러한 내부적인 반응은 더욱 광범위한 “순위 현상”을 구성한다. 고등 교육의 국제화나 시장화와 같은 요인을 바탕으로 순위 현상을 해석 할 수도 있지만, 순위가 관중에게 유도하는 반응도 그만큼 중요하기 때문에 이 글은 이를 설명하는데 초점을 맞출 것이다.

–

Despite university rankings’ short history, they draw a great deal of attention each time a major ranking is updated for the year. As rankings have grown popular and ubiquitous, critics have in turn expressed concern over the significance that university rankings appear to have to their audience, as well as the overall impact that they produce in higher education. For example: how do we know that the information found in rankings is accurate? Are university rankings misleading, and do we trust them regardless? How have those working in higher education responded to the existence of university rankings, and are these reactive tendencies a cause for concern? Rankings subconsciously but pervasively influence those involved in academia and higher education in general. Many universities have already made extensive changes to their academic and administrative structures in order to “perform” better in rankings, and this response from within academia constitutes part of a wider “ranking phenomenon.” Factors such as the internationalization and marketization of higher education goes some ways to explaining the ranking phenomenon, but equally important is the reactivity that rankings induce in their audience.

One story oft-retold among certain circles of higher education policy is that of what happened to a Malaysian university in the early 2000’s. The University of Malaya, Malaysia’s oldest university, was ranked 89th by the Times university ranking in 2004.[1] This achievement was lauded by the Malaysian media, and the university itself decided to splurge on banners placed both around and outside the campus to celebrate UM becoming a “top 100 university.” However, in the following year Times made changes to its methodology which now categorized the Chinese and Indian students at UM as being national rather than international students, causing UM to plummet to 169th in the 2005 ranking. Not only did this outcome damage UM’s reputation, but in the fallout of the incident, the Malaysian government decided not to renew the UM vice-chancellor’s contract: the VC, whose decision it had been to allocate university resources to advertising UM’s ranking performance in 2004, found himself personally taking the fall for 2005’s disastrous returns. Although UM’s academic or institutional quality hadn’t drastically changed between 2004 and 2005, the fact of the matter remains that UM experienced dramatic changes in fortune as dictated by an opinionated list assembled by a media outlet far removed from academia.

Figure 1. Banner advertising KAIST as one of the “most innovative universities” according to Reuters. Found on KAIST main campus

This story illustrates the absurd lengths to which some in higher education will go as a response to university ranking results. A prospective student for example may decide on which university to attend partly based on how high that university was most recently ranked; in similar fashion, a university executive may reward department A with additional funding taken from department B’s budget because department A helped raise the university’s ranking score while department B produced the opposite effect. Universities become increasingly mindful of how they perform in the most popular rankings because they are wary of the impact that these rankings can have on “consumers.” These consumers include individuals and organizations that each have a stake in higher education, such as prospective students, partners in industry, and government agencies, and the more consumers believe in the information that university rankings show, the more universities have to assume that rankings will impact how the consumers view each institution. Consequently, universities compete against each other to place higher in university rankings since the higher a university can climb in rankings, the more financial and reputational rewards it is likely to receive in the form of increased government and industry funding as well as increased application rates from better qualified students.[2] To that end, many universities undergo organizational changes that affect their spending, recruitment and even institutional missions.

How is it that something as seemingly innocuous as university rankings can so strongly impact major decisions in higher education? And even in the face of competition and pressure, how did rankings come to dominate everyone’s understanding of the lay of the land? University rankings are sometimes said to be “objective” because each university’s score or position on the rankings is allegedly calculated using a comprehensive and quantitative methodology; they serve as useful benchmarking tools for universities to size up their competitors and set their own institutional objectives; and lastly, because they are a convenient source of readily available and easily digested information for all audiences. However, these arguments lose credibility in the face of extensive criticism directed at university rankings. They also fail to suggest a more fundamental explanation for this “ranking phenomenon.”

[What are university rankings?]

The origin of modern university rankings is accredited to the late 20th century United States, when in 1983 US News and World Report first published a national rankings of universities, while the very first university reputational rankings were produced much earlier in 1925.[3] The focus of most university rankings has primarily been on undergraduate programs, as demonstrated by the relatively long history of the US News rankings of American colleges when compared to the National Research Council’s Assessment of Research Doctorate Programs, which was only released in 2010 and is the only comprehensive analysis of graduate programs in the US.[4] As for world university rankings, the standouts include: the Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU), the QS Rankings, and the Times World University Rankings. The ARWU was first published in 2003 by Shanghai Jiao Tong University and this first iteration compared over 1,000 higher education institutions worldwide and was intended to serve a benchmarking role. The QS-Times joint rankings followed suit in 2004, assessing British universities’ relative standings with foreign institutions. QS and Times split in 2009, after which point the Times rankings were produced independently.

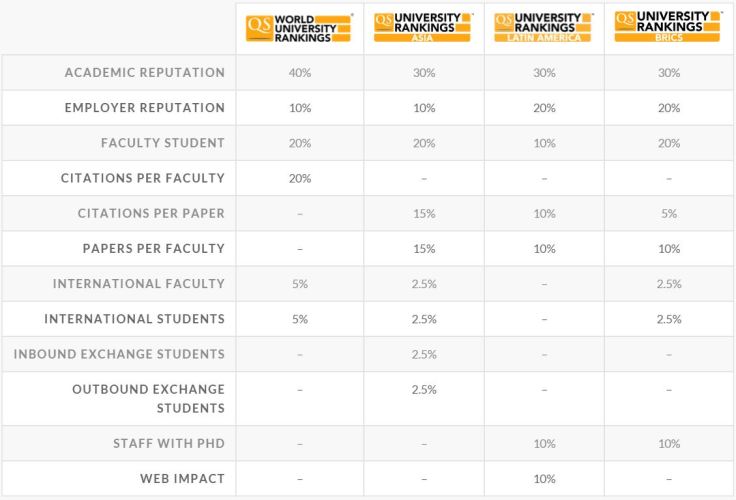

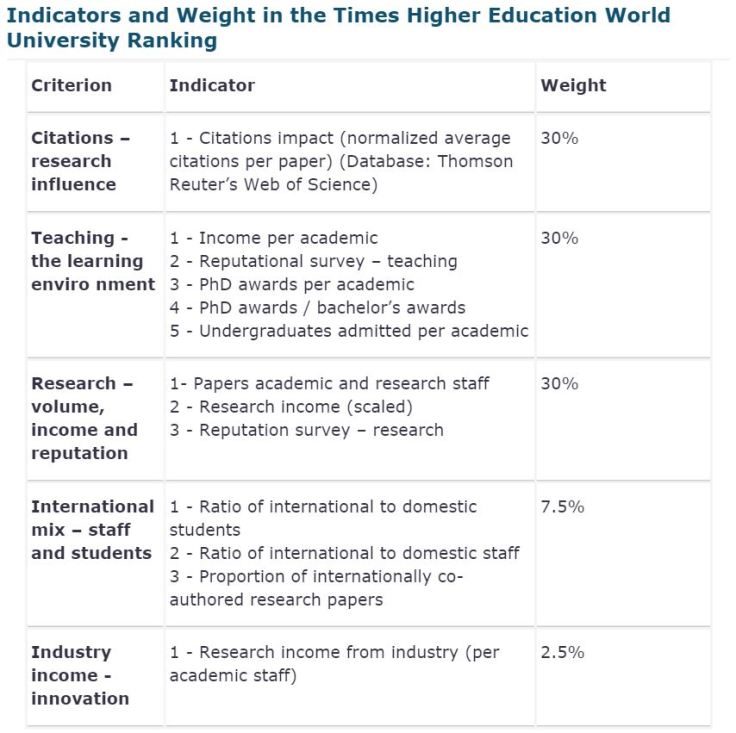

These major rankings feature several conventional criteria by which universities are evaluated, such as the volume and quality of research (measured by the number of publications and citations), internationalization (number of foreign faculty and students), and reputation (determined via surveys). Of course, no two ranking methodologies are identical: most notably, the QS and Times rankings rely heavily on reputation scores, while the ARWU employs only purely quantitative criteria, such as the number of faculty at an institution who have received a Nobel Prize or Field Medal, or the number of papers that faculty have published in Nature, Science, or other SCI/SSCI journals.

For all their methodological rigor and gradual refinement over the years, university rankings undoubtedly remain controversial. They have for instance drawn criticism for misleading consumers because contrary to their advertised image of objectivity, rankings have in fact been accused of possessing inherent biases that audiences can unwittingly pick up. Universities have in the past easily manipulated the statistics reported to ranking organizations in order to attain better scores, and reputation is so subjective a notion that many argue it ought not to be included as a criterion. Even in the case of “hard numbers,” the problem remains that numbers such as the student to faculty ratio or the number of renowned faculty are only proxies – and poor proxies at that – to represent the factor consumers really want to see: educational quality.

Figure 2. QS rankings methodology table[5]

Perhaps most damning of all is criticism of the concept of ranking universities. At a fundamental level, university rankings are criticized for being both heterogeneous and comprehensive.[6] Author Malcolm Gladwell is critical of the US News rankings since it (and many other national and world university rankings) not only tries to compare intrinsically different institutions, but does so on a whole suite of different measures for quality. Most university rankings are presented to their audience as a single listing that covers academic institutions of all types regardless of age, size, or institutional mission. In this sense the typical university ranking strives for heterogeneity because it uses a methodology broad enough to cover all institution types. The problem arises when rankings try to be simultaneously comprehensive by covering not just one aspect of quality, but all possible aspects of university quality, as criteria exist for teaching, reputation, research, and many others. The problem thus created is that rankings are neither trying to find the best out of a bunch of similar and comparative universities, nor are they trying to find the one university among all universities that stands out in a particular aspect of higher education. Attempting to grade every possible university on every possible measure of institutional quality is an active dismissal of the variety that can be found in academia, and the value that such distinction brings to higher education in general. Furthermore, such “all schools on all measures” approach undoubtedly favors large, rich, research-based universities above all other university types.

[The response to university rankings]

In light of such overwhelming criticism, it is difficult to perceive university rankings as anything other than a flawed object. And yet we find that in practice, stakeholders of higher education cannot escape from rankings’ influence. The case of a typical, middle-of-the-pack, private university located in Seoul[7] (which we shall refer to as “University A”) presents an honest portrayal of how universities have adapted to rankings. As previously mentioned, universities are strongly compelled to strategize their institutional policies, expenditures and focus in order to maximize their university rankings performances. Good outcomes in the latest rankings are imperative for universities lacking major funding or established reputations to survive because by placing high in these rankings, universities can secure more state and industry projects and (particularly relevant for Korean universities) ensure a larger pool of incoming student applicants at a time when freshmen cohort sizes are projected to sharply decline in the next several years.

University A is an institute that has found recent success in Korean university rankings, and it attributes this success to being better prepared and responding faster to the rankings trend than did its competitors. As part of their early response to university rankings, University A created a new administrative team – the evaluation team – in their institution headquarters. Since its creation, the evaluation team at University A has gained notoriety for how busy its staff are kept by their work, and is jokingly referred to as “the Samsung Electronics of the university,” or “the school staff’s graveyard.” They are in actuality given heavier workloads and face mounting pressures to assist in further improving the university’s rankings. The evaluation team is affiliated to the office of planning together with the strategy establishment and system improvement teams. These three teams are instructed to coordinate their activities: the evaluation team determines University A’s current situation with regards to various rankings, after which new strategies are formulated by the system improvement team to bring positive change to the university while the strategy establishment team plans out long-term university improvements. The head of University A’s office of planning has candidly stated that this restructuring is intended to better match general university strategies and planning to university rankings.

Figure 3. Times rankings methodology table[8]

Perhaps the biggest impetus for universities in Korea to systematically manage their rankings performances came in the late 2000s, when the government made changes to how state funding would be distributed. The new distribution method, which relies on formulaic funding schemes and evaluations-based distribution, induced universities to move away from standard day-to-day operations to instead operate on a selective concentration strategy. Each university now takes on tailor-made strategies specific to where it lies in rank – for example, lower-ranked institutions focus on government evaluations (which are naturally tied to governmental financial support schemes for higher education sector), and higher-ranked ones focus on their world rankings performances. As for University A, its response was to implement a “ranking taskforce” meeting – a biweekly event for university staff to meet and discuss university rankings, including discussion on the ways to improve scores in various criteria. Through these meetings, University A decided that the evaluation criteria used in Joongang Ilbo’s rankings are to be designated “key important indicators” for the university to closely monitor and manage. The decision to strategize along the Joongang Ilbo criteria was made because University A deemed that particular ranking to have more of a nationwide influence than others, and thus the most important target for the university to improve its performance.

Aside from the “big picture” moves, attention to detail makes up part of the universities’ efforts to improve their ranking performances. For their part, the staff at University A compiled a list of all the different spellings of the university’s name that had appeared in English publications and submitted this list to ranking organizations so as to minimize the possibility of publications by University A faculty from being omitted in the scoring process. Reputation surveys as previously mentioned make up a significant portion of scores for some university rankings, and University A takes care to manage an extensive contact list of academics worldwide to whom the university regularly sends PR material. The university also keeps a list of scholars who are most likely to assess University A favorably, and these scholars are then recommended to ranking organizations as potential reputation survey respondents.

University faculty are also affected by university rankings. Newly hired faculty at Korean universities are often referred to as the “SSCI 2.0 generation” since many of them had to publish two or more papers in prestigious journals to beat out their competitors for faculty positions. Universities see the ideal professor as someone who can help boost university research figures via research productivity, and this aspect appears to outweigh other factors such as teaching ability. Even after their appointment, faculty are constantly under threat of “publish or perish” that in practice limits their autonomy and diverts attention away from other traditional professorial roles including teaching and student mentoring. In the face of such pressures, faculty have had to acquiesce, and practices such as multiauthorship or the participation of graduate students in publishing, both hitherto almost unheard of in the field, have become more common practice among Korean sociology scholars.[9]

[Why we believe in rankings, and the future it holds for us]

In the mass of critical literature on university rankings, an overarching argument is that university rankings by their very existence exert a certain influence on the institutions, governments and other actors in higher education. The various changes and reactions brought about by this influence constitute the “ranking phenomenon” that we’ve thus far discussed. Central to understanding the ranking phenomenon is the concept of reactivity, which states that when they become aware of any measuring or evaluating, the actors under measurement will behave differently as a reaction to this knowledge. Essentially, measuring alters the subject of measurement if the subject is made aware of the measurement. Closely related to reactivity is the mechanism of the self-fulfilling prophecy. The self-fulfilling prophecy can be defined as a “confident error [that] generates its own spurious confirmation… a false definition of the situation evoking a new behavior which makes the originally false definition of the situation come true.”[10] University rankings are self-fulfilling prophecies because they elicit certain responses or reactions from people and organizations. Because university rankings present seemingly objective evaluations of the relative performance, quality, and value for each university, some consumers, especially those who are less familiar with higher education, accept them as good representations of reality and change their behavior accordingly. Furthermore, rankings affect not only these actors’ actions, but those of other stakeholders who must now account for the changes to the first group. The perceptional and behavioral changes to these groups is a clear example of the ranking phenomenon. Predictions found in rankings (i.e. the order in which universities are ranked) become a dynamic factor that “changes the conditions under which it comes true,” and that furthermore it “encourages behavior that conforms to it,” thus moving closer to the prediction.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

The third University Ranking Forum of Korea event, held in Seoul on October 15, 2015, saw a gathering of university faculty and staff with the purpose of “discussing and sharing information concerning the various university rankings’ criteria and methodologies, for the sake of universities’ development and increased competitiveness.” Among the forum’s presenters was Euiho Suh, professor at POSTECH Industrial and Management Engineering, whose presentation revealed much about his institution’s approach and stance towards university rankings.

Suh’s presentation, titled “The problem with university rankings’ publicity and its importance,” highlighted the difficulties in overcoming a lack of institutional reputation, as well as the tendency for such reputation to become harder to overcome over time. In this context of a fight against time for improving institutional reputation, Suh argues for ranking improvement strategies that focuses on improving the reputation aspect, which is a more time- and cost-effective strategy compared to improving research output figures or the student-to-faculty ratio. Suh is clearly working to improve his institution’s rankings and looks to involve POSTECH in global competition but just like University A, POSTECH finds itself having to strategize in compliance with university rankings.

If universities and other stakeholders in higher education continue to find themselves unable to move away from university rankings, the unwelcome influences of the ranking phenomenon will persist. Universities are already trending dangerously towards homogeneity, as every university looks to become the stereotypical large-sized, research-oriented, internationalized “world class” institution. It is of vital importance that questions on the mission of the university, as well as its values and roles in higher education are not further determined by rankings alone.

읽을거리

The Economist (Special feature: “The whole world is going to university”, March 28, 2015)

This special feature on higher education brings up a worrying possibility that universities in practice provide little to no real knowledge to its students, and instead serve as an elaborate and expensive sorting mechanism to pick out talented individuals for industry. Also, whereas governments worldwide share a vision of higher education that meets a societal need – that universities produce human capital needed to drive the modern economy and create intellectual property – its implementation various greatly between nations. Which is right for higher education: elitism or egalitarianism?

Malcolm Gladwell, “The Order of Things”, New Yorker editorial, February 14 & 21 issue, 2011

(https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/02/14/the-order-of-things)

Check out Gladwell’s New Yorker piece to get a better understanding of the fundamental limitations of rankings, as well as the concept of the self-fulfilling prophecy.

W.Y.W Lo, University Rankings Implications for Higher Education in Taiwa, Springer, 2014

This book discusses at great depths the geopolitical concerns associated with university rankings. Relying on concepts such as neocolonialism and soft power, Lo paints a picture of strong and often Western “centers” of higher education to which “peripheral” nations and institutions gravitate towards and model themselves after. In this view, Asian universities are drawn by the subtle but attractive forces found within university rankings, the result of which is that Asian universities voluntarily compete under conditions that are inherently disadvantageous to them.

[1] Marginson, S. (2006), “Global university rankings at the end of 2006: Is this the hierarchy we have to have?” OECD/IMHE & Hochschulrektorenkonferenz.

[2] Shin, J.C. & Harman, G. (2009), “New Challenges for Higher Education: Global and Asia-Pacific Perspectives”, Asia Pacific Education Review, Vol. 10(1), pp. 1–13.

[3] Dill, David D. (2006), “Convergence and Diversity: The Role and Influence of University Rankings.” Consortium of Higher Education Researchers 19th Annual Research Conference.

[4] Altbach, P. G. (2012), “The Globalization of College and University Rankings”, Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, pp. 26-31.

[5] QS Top Universities, https://www.topuniversities.com/

[6] Gladwell, M. (2011), “The Order of Things”, The New Yorker.

[7] 전현식 (2014), “대학랭킹문화: 문화기술지적 탐구”, 경희대학교 석사학위논문, p.120

[8] Times Higher Education World University Rankings, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/methodology-world-university-rankings-2016-2017

[9] 한준·김수한 (2017), 「평가 지표는 대학의 연구와 교육을 어떻게 바꾸는가: 사회학을 중심으로」, 『한국사회학』, 제51집 제1호, pp. 1-37.

[10] Espeland, W. N. & Sauder, M. (2007), “Rankings and Reactivity: How Public Measures Recreate Social Worlds”, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 113(1), pp. 1-40.

댓글 남기기